One of the more common questions I get asked by non-audiologists is: “How do you test a baby’s hearing?”

The answer is two-fold. We don’t test hearing, but audiologists can test hearing function and speculate about hearing ability based on information from a series of tests.

What do you mean?

Hearing is the individual perception of sound that may or may not generate a reaction. Your husband can hear you yelling at the TV during an exciting football game and he may choose not to say anything. Your dog may hear you call his name and may start to wag his tail or walk toward you. Hearing is subjective and the responding behavior will usually indicate if you’ve been heard.

When performing a hearing test, audiologists rely on patient’s behavioral responses to sound in order to determine the type and severity of his or her hearing loss. Whether that be a verbal response (e.g. “yes”), a push of a button, or a hand raise – some sort of response must serve as an indicator that the patient heard the soft beeps. This method of testing works well for adults and children who are 5 years or older (there are exceptions, which will be discussed later).

I would be asking too much from a baby to raise their hand every time a sound is heard. Some babies can barely hold their head up at 6 months of age. In order for audiologists to measure hearing for newborns or young children, we have to utilize other tools to get the job done.

What is normal auditory function?

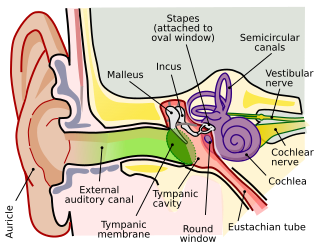

Instead of measuring ‘hearing’, we measure auditory function in babies. Auditory function refers to the capability of the ear structures or anatomy to process sound and facilitate hearing. We hear with our brain, not just with our ears. Audiologists assess the pathway of sound through the outer ear, middle ear, inner ear (also known as the cochlea), the hearing nerve (VIIIth cranial nerve) up to the brain to form an impression about how well a baby can hear.

Universal newborn hearing screening

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), approximately 2 to 3 out of 1000 children are born with hearing loss. Over the course of time, studies have shown that late-deafened, or late identified hearing loss resulted in children falling behind in speech and language development compared to their normal hearing peers in the classroom.

Something needed to be done to address the prevalence of hearing loss among the pediatric population. In the early 1990s, a group of important people came together to advocate for early identification of hearing loss in babies and early intervention and management for children with a hearing impairment.

The implementation of universal hearing screenings across the United States encouraged birthing hospitals, primary care physicians, pediatric health care facilities to identify hearing loss in babies within the first 3 months of life.

Methods of hearing screening

There are a couple ways to screen for hearing loss after the birth of a newborn. Again, these are screening tools that assess auditory function. They are not a test of hearing.

Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE)

This screening takes minutes, at most, to check both ears. A nurse or technician inserts a tip into your baby’s ear. The tip sends several beeps and sounds (imagine sounds like robots speaking in Morse code) into the ear. Your baby’s inner ear (or cochlea) will produce its own sounds (emissions) in response, and those emissions are measured and analyzed by the tip’s microphone in the ear.

Healthy inner ear responses will generate a “pass” for the hearing screening. If the inner ear responses are non-existent or hardly present across different pitches, this will prompt a “refer” for your baby to be re-screened or flagged for additional follow up testing.

Just so you know, this is not an ear echo. Otoacoustic emissions are sounds generated from a healthy cochlea to indicate normal functioning sensory [outer] hair cells necessary for hearing.

Sometimes, a “refer” result is due to fluid in the middle ear preventing the initial sounds from reaching the cochlea in the first place. Makes sense, right? Your baby has been swimming around in a fluid-filled space for 9 months, so the fluid needs to clear out of their ears after birth to be able to generate the emissions. Your baby’s ears will need to be re-screened to determine whether a “refer” result is associated with middle ear fluid.

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR)/Auditory Evoked Potential (AEP)

This screening takes longer than a few minutes to complete because of the prep work involved. Audiologists perform this type of hearing screening and it is typically for babies staying in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Premature births, congenital cytomegalovirus, and babies born with breathing or heart problems are several reasons why a baby might carry a higher risk for developing hearing loss. Birthing is truly a miracle, but it can also be unpredictable when complications affect your child’s hearing health.

For this screening, the audiologist will scrub your baby’s forehead and the area behind both ears before placing small stickers on the skin. These stickers are called ‘electrodes’, which are used to measure your baby’s electrical brain activity in response to clicking sounds. The clicking sounds are presented through a tip placed in your baby’s ear.

ABR screening is non-invasive, it does not hurt, and is typically done while your baby is asleep. Your baby’s restful state is necessary to allow for the best response recording possible.

Your baby’s brain activity is analyzed in the moment to assess whether the brain pathway for hearing is functioning. We can assess whether the hearing nerve is responsive to the clicking sounds to screen for the possibility of hearing loss. Like the OAE screening, the ABR screening can generate a “pass” or “refer”. A response is either present (pass) or not present (refer). If your baby gets a “refer” result, you will need to pursue further follow-up regarding your child’s hearing to complete diagnostic testing.

“Refer” does not mean fail

I’m not a parent, but as a human who is admittedly not as perfect as I always hope, I know that failing anything is never a good feeling. With regard to newborn hearing screenings, I try really hard not to use the word “fail” with my new parents and their babies because it is hard to process that your child has already “failed” something in their first few days of life.

Simply, a “refer” result means you baby needs to undergo further testing. Your baby is not automatically deaf just because they didn’t pass the hearing screening. Your baby got a “refer” result because we don’t have enough information to suggest that their cochlea(s) function the way we would expect. It is absolutely possible for your baby to get a “pass” in one ear and a “refer” in the other ear. My advice? Follow up and get both ears checked out.

Using ABR as a diagnostic test

The great thing about ABRs is that it is also a diagnostic tool. It is used to test the response of the hearing (auditory) nerve at various sound levels (think: volume). Audiologists use ABR testing to approximate thresholds of possible hearing ability at different pitches. It is used often with babies and children who cannot sit through traditional hearing tests, which require behavioral responses.

ABR testing is an amazing tool and can provide a lot of information about auditory function. While it can’t replace traditional hearing tests, it is a reliable way to bridge the gap of time when a baby or young child can’t raise their hand during hearing tests to when they can participate behaviorally.

1-3-6 benchmark is on its way to 1-2-3

Previously, I mentioned that a group of very important people came together to advocate for early identification and intervention for children with hearing loss. They are known as the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) and they have been promoting a 1-3-6 benchmark for universal infant hearing screening, diagnosis, and early intervention services.

To break it down, the goal is to screen infants within 1 month of birth, obtain audiologic diagnosis by 3 months, and enroll in early intervention services by 6 months of age.

Early intervention services are monitored at the state level through Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs. Early identification of hearing loss is meant to facilitate early intervention to provide every child with a hearing loss access to language. Discussions about language and communication goals for the family are necessary to determine the appropriate course of action.

Based on countless research studies about speech and language development (some studies referenced below), babies with access to early intervention services and appropriate hearing amplification/technology (e.g. hearing aids or cochlear implant) have better outcomes with developing spoken language skills during their critical years compared to babies without early intervention.

We know that early is better. JCIH is now suggesting a 1-2-3 month timeline: infant screening by 1 month, audiologic diagnosis by 2 months, and enrollment in early intervention services by 3 months of age. That, coupled with a recent announcement that infants with severe to profound hearing loss can now safely receive a cochlear implant as early as 9 months of age encourages more natural spoken language development.

Final Points

Hearing loss affects people of all ages, including children. Universal hearing screenings have helped identify babies that need a more comprehensive hearing assessment earlier.

Although the first few months of caring for a newborn is stressful (stressful is likely an understatement), it is important to follow up with hearing referrals if developing spoken language is a priority for you and your child.

If your child is diagnosed with hearing loss during these follow up appointments, know that he or she is not alone. There are many community resources (including early intervention specialists) available to help your family navigate the challenges associated with raising a child with hearing loss. This can be a very emotional process and there’s no right or wrong way to feel about your child’s diagnosis.

Understanding hearing loss is a journey. Knowledge is power.

In addition to community resources, many parents raising children with hearing loss have shared their stories on social media. Perhaps following their stories can help you feel more empowered.

Last, but not least: some babies who “pass” newborn hearing screenings may have mild hearing loss. Hearing screenings are fast and may not always pick up milder forms of hearing loss. If you suspect that your child has hearing problems or delayed speech and language development, bring him or her in for a hearing test as soon as possible to find out.

References

Ching, T. Y. C., Dillon, H., Marnane, V., Hou, S., Day, J., Seeto, M., . . . Yeh, A. (2013). Outcomes of early- and late-identified children at 3 years of age: Findings from a prospective population-based study. Ear & Hearing, 34(5), 535–552.

Early Identification of Hearing Impairment in Infants and Young Children. NIH Consens Statement 1993 Mar 1-3;11(1):1-24.

https://consensus.nih.gov/1993/1993HearingInfantsChildren092html.htm

Johnson, J. L., White, K. R., Widen, J. E., Gravel, J. S., James, M., Kennalley, T., Holstrum, J. (2005a). A multicenter evaluation of how many infants with permanent hearing loss pass a two-stage otoacoustic emissions/automated auditory brainstem response newborn hearing screening protocol. Pediatrics, 116(3), 663–672.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. (2019). Year 2019 position statement: Principles and guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention programs. The Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention; 4(2): 1-44. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=jehdi

Karltorp E, Eklöf M, Östlund E, Asp F, Tideholm B, Löfkvist U. Cochlear implants before 9 months of age led to more natural spoken language development without increased surgical risks. Acta Paediatr. 2020 Feb;109(2):332-341.

Kuhl PK. Early language acquisition: cracking the speech code. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(11):831-843.